“Wales is not a nation in the medieval sense, but it is also not nothing.”

– paraphrased from every seminar I have ever attended on early medieval Britain.

To study Wales is to study absence. Not absence of people, of course — the valleys, coasts, and mountains were full of them — but absence of boundaries, of the neat political and linguistic containers that modern historians like to use. “Wales” did not exist as a coherent entity until the late medieval period, and even then, its identity was largely constructed by those beyond it. The very name comes from wealas — “foreigners” — a word used by the Anglo-Saxons to describe the Brittonic-speaking peoples to their west. In other words, Wales begins as someone else’s category.

Want to read more? Subscribe to follow the project and its ongoing conversations.

Studying Wales is difficult not simply because sources are fragmentary or the archaeology uneven, but because the conceptual frameworks we bring to the topic are shaped by later politics. When historians talk about England, they can point to emerging central institutions, written records, and kings who ruled from somewhere. Wales offers none of that tidy infrastructure. Instead, it is a mosaic of kingdoms — Gwynedd, Powys, Dyfed, Brycheiniog — whose boundaries flexed with alliances and family feuds, and whose rulers often had more in common with their Irish or Cornish counterparts than with the centralised monarchies of the continent.

The Colonial Lens and Its Discontents

Modern scholarship often describes medieval Wales through the language of empire and resistance: England’s first colony, a frontier society, a land subdued. This framing is not entirely wrong — conquest and subjugation did happen, and their scars remain etched into both material and cultural memory — but it risks retrofitting modern political ideologies onto a world that did not think in those terms. Colonialism presumes a coherent state with fixed borders and an articulated ideology of control; eleventh- and twelfth-century England, recently Normanised itself, was hardly such a state. Its kings were still experimenting with governance, and its aristocracy was far from ethnically or culturally uniform. To say Wales was “colonised” by England in this period is like saying two river currents collided and one called the other wet.

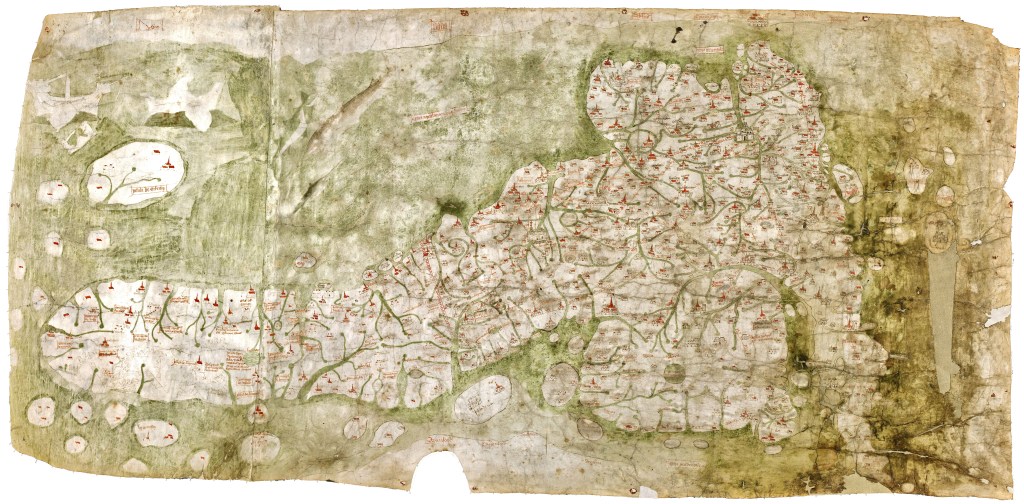

The Gough Map; a Late Medieval Map of the island of Great Britain. North lies to the left of the map.

The language of colonialism persists because it offers a moral clarity that early medieval history resists. It provides heroes and villains, oppression and defiance, and it feels narratively satisfying — especially in a post-industrial, post–miner’s-strike Wales where questions of identity and Englishness still burn hot. The danger is that such frameworks flatten the past into allegory. The early medieval Welsh were not proto-nationalists; they were power brokers. They negotiated, married, traded, and occasionally raided their neighbours — as all early medieval communities did. To call that resistance or subjugation is to impose a later emotional geography onto a landscape that did not yet have one.

Identity as Negotiation

One of the most revealing features of early medieval Wales is the permeability of its identity. Names, titles, and even visual symbols moved fluidly across cultural boundaries. After the Norman conquest, Welsh elites adopted Norman-style heraldry and naming conventions — not simply because they were conquered, but because these practices carried social capital. The use of fitz– patronymics or armorial bearings was a means of participating in an aristocratic language of prestige shared across Britain and northern France. Adoption, in this context, was strategy, not surrender.

Equally, Norman settlers in the Welsh Marches frequently “went native,” taking Welsh names, marrying into local families, and incorporating local saints into their devotional calendars. By the thirteenth century, it is entirely normal to find marcher lords named Rhys or Llewelyn whose ancestry includes as many French knights as native princes. The border was not a wall; it was a conversation. Cultural identity was not a binary of Welsh versus Norman but a gradient of belonging negotiated through land, marriage, and language.

To call this process “assimilation” or “resistance” misses the point. People did not perceive their behaviour as ideological. They were navigating opportunity, positioning themselves advantageously within overlapping hierarchies of lordship and legitimacy. The permeable identity that makes Wales difficult to study also made it resilient.

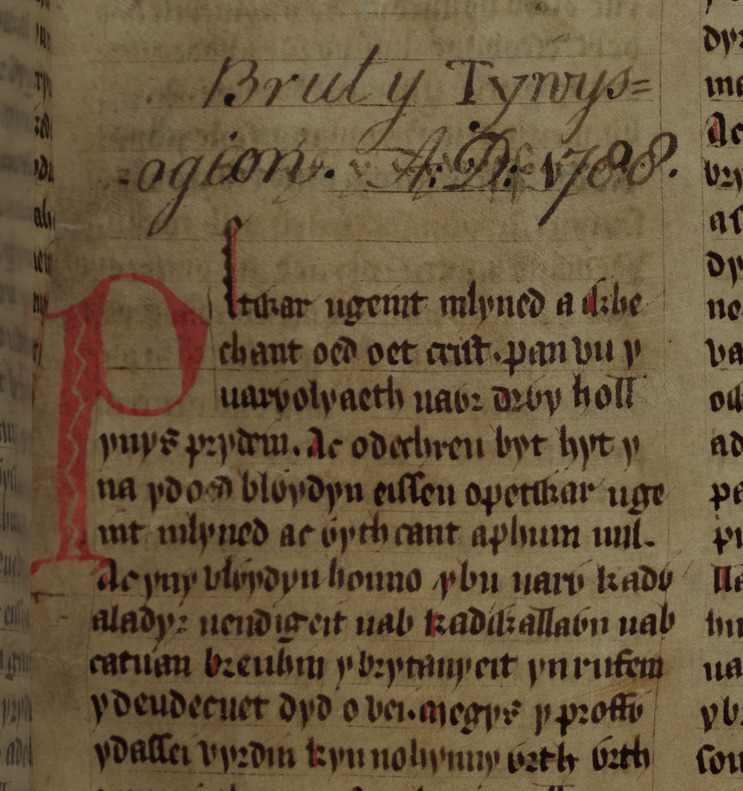

The opening lines of Brut y Tywysogionfrom the Red Book of Hergest

The Problem of Sources

The practical difficulty of studying Wales lies in its sources — or, more precisely, the imbalance between what survives and what was valued. Anglo-Saxon England left charters, law codes, and monastic records; Wales left poetry, genealogies, and chronicles that often blur myth and memory. The Historia Brittonum and Annales Cambriae provide outlines, not clarity. The Mabinogion offers something deeper but stranger: myth as social commentary, history as cultural dreamwork.

Archaeology helps, but even here, the record is uneven. Excavations at Llangorse, Dinas Powys, and Degannwy hint at royal courts, trade, and craftsmanship — but not the bureaucratic footprint we find east of Offa’s Dyke. Much of early Welsh history simply wasn’t written down at all, not because it didn’t exist, but because it belonged to a spoken tradition. The early medieval Welsh valued oral memory, poetic recitation, and genealogical storytelling as tools of legitimacy and continuity. Kingship itself could be performed through recited descent; the bardic class preserved law, history, and reputation through verse rather than parchment.

Modern scholarship privileges written evidence, and so when the Welsh historical record “goes quiet,” it is not that Welsh culture disappeared — it is that our tools for hearing it fail. The absence has often been misread as deficiency. The lack of law codes or cathedrals becomes evidence of “underdevelopment,” but such judgments reveal more about historians than about history. A society’s intelligence is not measured in parchment thickness. Wales’s record looks thin only if measured by English standards — and that is precisely the mistake early scholars made.

English Frameworks, Welsh Realities

The first historians of medieval Wales were English antiquarians who viewed the region through an imperial lens. By the nineteenth century, this had hardened into ideology: Wales as a picturesque backwater, a quaint remnant of a purer past. The twentieth-century nationalist revival rightly rejected this narrative, but often by inverting it. Wales became not a conquered land but a colonised one. Both interpretations rely on the same binary: powerful centre, passive periphery.

The reality was more complicated. Welsh rulers such as Hywel Dda in the tenth century actively shaped law, governance, and trade within a broader Insular context. Welsh bishops attended synods; Welsh artisans adapted continental forms. Political subordination and cultural sophistication could coexist — as they did across Europe. To describe Wales as merely “acted upon” is to deny its agency, but to describe it as isolated is equally inaccurate. Wales participated in — and helped shape — a continuous web of exchange.

The Modern Filter

The study of Wales often doubles as a study of Welshness. Every historian carries an inherited vocabulary — nation, identity, oppression, survival — shaped by more recent histories: industrial decline, linguistic revival, devolution politics. These frameworks help us empathise with the past but can also distort it. They encourage us to read medieval Wales through a lens polished by much later anxieties.

Take the common phrase “England’s first colony.” It captures the enduring inequality between Wales and England, but when applied to the early medieval period, it risks turning cultural complexity into political morality. “Colony” implies a metropolitan centre projecting power onto a periphery; yet in the twelfth century, “England” was scarcely coherent, and “Wales” consisted of mutually competing polities. Mapping modern political categories onto this landscape is like mapping parliamentary constituencies onto constellations — it imposes coherence on a sky that never had it.

Postcolonial theory provides powerful tools, especially for analysing how identity is constructed through language and power, but it must be used with care. A Norman knight calling a Welsh ruler rex or princeps was not imposing a foreign hierarchy; he was translating a local one into his own idiom. That translation is not colonialism but multilingual pragmatism, a negotiation of status between aristocracies who were more alike than their later national narratives admit.

This tension between modern identity and medieval evidence is not only academic — it is personal. Growing up in Wales, the study of Welsh history was often framed through the cultural tropes of the miners’ strike, the language movement, and Welsh nationalism. In school, Welsh history was something you either embraced as an act of patriotism or avoided to sidestep being labelled a nationalist. I fell into the latter category, not out of disinterest but out of discomfort: I did not want my curiosity about the past to be read as a political statement. Many of my peers felt the same. It is only later — including in my dissertation — that I returned to Wales as a historical subject, realising that the medieval past is not owned by nationalism, and that avoiding it ceded interpretive space to precisely the narratives I wanted to think beyond.

Understanding medieval Wales, then, requires both scholarly and emotional recalibration: a willingness to bracket modern identities without ignoring how powerfully they shape our questions. The past should not be flattened into either grievance or nostalgia. It demands an attentiveness that resists the comfort of ready-made categories — including those handed to us by our own upbringing.

The Archaeology of Ambiguity

Material culture reinforces this picture of fluidity. Excavations in the border regions reveal surprising hybridity: pottery styles, building techniques, and burial customs blending native and continental traditions. At Llantwit Major, imported Mediterranean goods appear alongside locally made artefacts — evidence of trade networks stretching far beyond England. In the Marches, timber halls evolve into stone keeps, but local motifs persist in decorative carvings and church dedications. Archaeology refuses to pick sides.

What emerges is not a story of imposition but of translation — literal and metaphorical. Power was communicated as much through shared aesthetics as through force. A cross carved in a Welsh church may have been inspired by Norman models, but the saint it commemorated was local. The architecture speaks bilingual.

Wales as Method

Perhaps the hardest thing about studying Wales is not what it lacks, but what it reveals about how we study. It exposes the fragility of our categories — “nation,” “colony,” “identity,” “continuity” — all of which Wales refuses to sit neatly inside. Examining early medieval Wales forces historians to confront their own assumptions and to ask whether the tools we use to study empire, reform, or conversion elsewhere can survive contact with a landscape whose boundaries were porous and whose evidence was poetic.

The early Welsh world reminds us that not all history was written. Some of it was sung, performed, remembered. Wales is not unknowable; it simply demands different methods. Reading medieval Wales requires comfort with contradiction, with ambiguity, with the spaces between language and power. Wales resists being studied because it resists simplification. The historian’s task is not to dissolve that resistance but to work within it — to treat uncertainty not as failure but as knowledge.

Wales, Then and Now

The modern nation is acutely aware of its historical marginalisation — both in the academia and within the wider UK. Welsh history is often taught as a regional subset of “British history,” its distinct voices smoothed into English narratives of progress. Yet the early medieval past, precisely because it is so slippery, offers a kind of freedom. It reminds us that identities are always made, never given; that belonging is contingent; that “Wales” has always been plural — a network of affinities, languages, and loyalties overlapping like ridges on a map.

Perhaps that is what makes Wales difficult to study and harder still to write about: to study it honestly is to admit that our categories are temporary. But that difficulty is also Wales’s gift. It asks us to think relationally — to see power, culture, and identity not as fixed points but as moving parts of the same weather system.

Want to read more? Subscribe to follow the project and its ongoing conversations.

Want to Read More?

- Davies, R. R. The Age of Conquest: Wales 1063–1415. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991. — The definitive account of medieval Welsh political and social transformation under Anglo-Norman influence.

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. Wales and the Britons, 350–1064. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. — A detailed study of early medieval Brittonic identity, law, and kingship before Normanisation.

- Brady, Lindy. Writing the Welsh Borderlands in Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017. — Examines how Anglo-Saxon literature imagined the border with Wales, challenging modern ideas of separation.

- Fulton, Helen, and Des E. M. Probert, eds. Seals and Society: Medieval Wales, the Welsh March and the Welsh Sea. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2018. — Explores documentary culture and identity in the Marches through the lens of charters and seals.

- Griffiths, R. A., and P. R. Schofield, eds. Medieval Wales and the Marcher Lords. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2008. — Essays on lordship, governance, and cultural hybridity across the Anglo-Welsh frontier.

Leave a comment