The cross is one of the most instantly recognisable symbols in the modern world. It appears on churches, flags, and jewellery; to contemporary eyes, it seems almost inseparable from Christianity. Yet in the early medieval period — roughly between the fifth and ninth centuries — the cross did not necessarily mean what we now assume it does.

Want to read more? Subscribe to follow the project and its ongoing conversations.

To see a cross on a brooch, a sword pommel, or a grave-gift and to conclude Christian is to misread an entire visual language.

Symbols, like languages, have dialects and contexts.

To an early Anglo-Saxon, a cross could signal allegiance to powerful Christian neighbours, participation in continental prestige networks, or even a visual shorthand for order and authority — without implying personal faith in Christ.

This essay examines how the cross functioned within early medieval symbolic systems, tracing how it moved from political shorthand to personal creed, and why conflating the two obscures the complex reality of conversion.

Conversion as Contact

The traditional story of Christianisation in Anglo-Saxon England begins with Gregory the Great’s mission of 597 and ends in the triumph of the Church. Yet archaeology has always troubled this neat chronology.

Excavated graves from the late sixth and early seventh centuries — especially female burials — reveal a blend of imagery: garnet-inlaid crosses, Christian motifs beside pagan ones, and textiles woven with patterns that could be read both ways.

Take the famous Trumpington Cross from Cambridgeshire (early seventh century).

A beautifully crafted gold-and-garnet pendant, found on the chest of a richly buried young woman, its equal-armed form and central boss unmistakably recall Mediterranean Christian models.

Yet its very form also fits comfortably into the broader world of continental elite ornament — circular pendants with radial symmetry were already status markers in Frankish and Alemannic graves.

Was this woman Christian? Possibly. But her cross also communicated something beyond belief: it placed her within a network of elite exchange that reached across the Channel, signalling access to Frankish luxury, continental diplomacy, and royal patronage.

And here lies the key ambiguity: was the cross an expression of personal faith, or a family’s display of prestige?

Grave-goods often speak as much to the living as to the dead. Burying a daughter with such an object could assert a family’s continental connections, advertise their participation in elite symbolic economies, or simply showcase wealth in a moment of public mourning. A cross in this context may have operated as bling as much as belief — a visual shorthand that blended piety, status, and aspiration in ways the archaeological record cannot easily disentangle.

Front and back views of the Trumpington Cross.

Crosses as Currency

IIn the sixth and seventh centuries, the political geography of north-western Europe was defined by asymmetry. The Merovingian and later Carolingian kingdoms dominated continental prestige economies, exporting not only goods but imagery. Anglo-Saxon elites, emerging from a patchwork of local polities, competed for continental recognition — and adopting the visual vocabulary of Christian Europe was one way to claim it.

The cross thus functioned as a prestige marker, not necessarily a confessional one. It appeared on sword fittings, disc brooches, and coins because it denoted participation in a world of power centred on the Franks and Byzantines. The political semiotics were clear:

wearing a cross signalled that one was plugged into the networks of legitimacy that governed exchange, diplomacy, and status.

This dynamic is visible in other frontier contexts. In Scandinavia, cross-like pendants predate formal conversion by centuries. In Merovingian Gaul, crosses adorned belt buckles and brooches as signs of courtly fashion, not necessarily piety. And crucially, this kind of symbolic borrowing has historical precedent well beyond the early medieval conversion period. In the Marcher lordships of medieval Wales (12th–13th centuries), Norman aristocrats adopted Welsh personal names, patronymic systems, and even heraldic motifs — not out of assimilationist sentiment, but as a strategic performance of belonging. By appearing “more Welsh,” they gained legitimacy, local support, and smoother governance. The Welsh, in turn, adopted Norman names and administrative styles, creating a hybrid political culture in which identity was negotiable, strategic, and materially expressed. Sources like the Annales de Margan (the Margam Annals) make this cultural entanglement clear: elite families actively reshaped their outward identity to optimise their position in a shifting hierarchy of power.

The same logic applies to early Anglo-Saxon England.

Adopting Christian imagery could be a way to show allegiance to powerful neighbours, participate in continental prestige systems, or visually claim a place within the wider Christianising world — long before personal belief caught up. Archaeologists have long recognised this ambiguity. As Martin Carver argued, conversion was not a singular event but “a negotiation through objects.” The cross could mediate between the symbolic grammars of the old and new orders, its meaning shifting according to audience old and new orders, its meaning shifting according to audience.

The Problem of Reading Faith Through Form

Archaeologists face a recurring temptation: to translate form into belief. If a burial includes a cross, it is labelled Christian; if not, pagan. But this binary collapses the semantic range of early medieval symbolism.

A brooch shaped like a cross might invoke protection, social rank, or a family emblem. A sword with a cross-shaped guard could be described as “cruciform” without being devotional. Even funerary orientation — such as east–west graves — can derive from broader cosmological traditions rather than explicitly Christian doctrine.

The early medieval viewer lived within a world of semiotic multiplicity, where the same motif could operate simultaneously on political, magical, and religious registers. The mistake of modern interpretation is to isolate one meaning at the expense of the others.

Catherine Hills once observed that “conversion in the ground precedes conversion in the soul.”² That is, material culture often anticipates theology. Communities experimented with Christian imagery before Christian practice had fully taken root, using symbols to test or perform affiliation long before belief itself transformed.

This insight matters because it reframes the archaeological record not as a simple timeline of belief, but as a dialogue of symbols — some inherited, some aspirational, some ambiguous, and some misunderstood.

Aesthetics and Appropriation

To understand the cross’s early appeal, we must also recognise its aesthetic power. The cross is an inherently geometric and balanced form — visually stable, adaptable to metalwork, and easy to replicate. Its structure aligned naturally with the design logics of early medieval art, which prized symmetry, interlace, and radiant patterning. Far from appearing foreign or intrusive, the cross could slot seamlessly into existing artistic vocabularies.

In the workshops of Kent or East Anglia, metalworkers would have encountered cross-forms not as alien Christian imports but as shapes that resonated with native traditions of radial ornament. The equal-armed cross, for example, merges easily with solar or wheel motifs found across pre-Christian northern Europe. This aesthetic overlap allowed the symbol to travel without friction — and without necessarily carrying theological weight. The appeal of the motif, in other words, could be visual long before it was doctrinal.

The art historian George Henderson described this process as “translation by design”: Christian forms reinterpreted through local artistic grammars. A Frankish reliquary cross might be copied in England not to proclaim orthodoxy but to imitate the luxury aesthetic associated with royal courts and continental patronage. The intent was often aspirational, not devotional.

This is why so many “conversion-period” artefacts appear hybrid: a cross set within animal interlace, a Christian motif rendered through the visual idioms of pagan art. These objects are not signs of incomplete or incoherent Christianity; they are instances of visual bilingualism. Their creators worked in a symbolic landscape where motifs could hold multiple meanings at once, and where aesthetic pleasure, political signalling, and emerging religious identity coexisted in a single form.

From Symbol to Statement

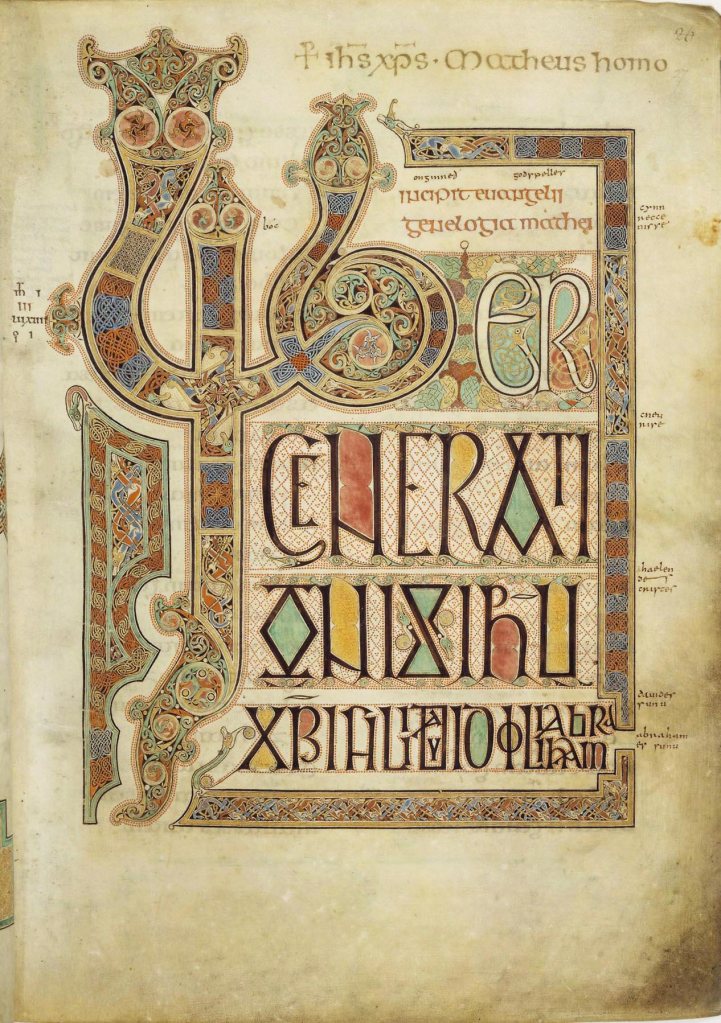

By the eighth century, as monastic centres such as Wearmouth–Jarrow and Canterbury rose to prominence, the meaning of the cross began to stabilise. Liturgical practice, the proliferation of iconography, and the production of illuminated manuscripts — most famously the Lindisfarne Gospels — collectively redefined the symbol as explicitly Christological. The cross now carried theological specificity: it invoked the Passion, sacrificial kingship, and the evolving devotional vocabulary of the early English church.

Yet even in this period of consolidation, politics remained inseparable from piety. The Ruthwell Cross in Northumbria (early eighth century) stands as a monumental negotiation between the sacred and the sovereign. Its runic inscriptions, drawn from The Dream of the Rood, entwine heroic language with salvation theology. Christ is depicted not as a passive sufferer but as a warrior-lord who “embraces the gallows as a brave man meets his fate.” This is a Christianity articulated through the idiom of Anglo-Saxon lordship — a synthesis that recasts the Crucifixion in the vocabulary of honour, loyalty, and heroic self-offering.

In this blending of devotional meaning and political aesthetics we glimpse the final stage of the cross’s transformation: from a sign of aspirational affiliation to a fully integrated expression of local belief. But the journey was neither linear nor complete. Even in the ninth century, the symbol retained residues of its earlier polyvalence. On coins, charters, textiles, and portable objects, the cross continued to function as shorthand for legitimacy — the divine sanction of rule — as much as a declaration of personal faith. Its meanings multiplied rather than narrowed, reflecting the layered identities of the communities who adopted it.

Folio 27r from the Lindisfarne Gospels contains the incipit from the Gospel of Matthew.

The original Canterbury cross

Crosses, Continuity, and Power

The persistence of ambiguity in cross symbolism reminds us that Christianity did not replace paganism overnight; it absorbed, repurposed, and re-coded it. This was not a uniquely Anglo-Saxon dynamic. Across the Mediterranean and Near East, similar processes unfolded as new religious systems appropriated the visual languages of older ones.

In late antique Syria and Egypt, for instance, the cross inherited elements from earlier solar and imperial motifs. When Constantine adopted the labarum — the chi-rho military standard — in the fourth century, he was drawing on a long tradition of cosmic iconography: the sun, the orb, and the axis mundi. These symbols had long conveyed sovereignty, cosmic order, and imperial legitimacy.

The Christian cross thus entered Anglo-Saxon England already carrying centuries of political utility and visual resonance.

in wider contexts across the early medieval world, Christianity frequently took root not by erasing older symbolic systems but by absorbing and reframing them. One striking example is the depiction of Christ with three faces — a visual attempt to express the Trinity that drew upon longstanding iconographic traditions such as the Roman god Janus, whose double or triple faces signified temporal mastery and divine oversight. While later condemned as heretical, these images reveal how Christian theology was initially communicated through a familiar visual grammar.

By the time it appeared on pendants, coins, or seals in early medieval Britain, the cross did more than signal belief. To inscribe it on a coin or a seal was to align oneself with the universalising claims of empire; to bury a pendant cross with a noblewoman was to situate her within a cosmology of authority that stretched from Rome to Reims. The symbol participated in a pan-European grammar of power, one in which political aspiration and religious expression were often inseparable.

This is why reading crosses as mere tokens of faith misrepresents the cultural mechanics of early medieval Europe. Conversion was not a simple binary of pagan versus Christian but a continuum of aspirational participation — a desire to appear Christian, to join the symbolic “club” of continental power before doctrinal commitment fully crystallised.

In this sense, the cross functioned much like Latin itself: a prestige language adopted first for diplomacy and legitimacy, and only later, gradually and unevenly, for devotion.

Case Study: The Trumpington Cross Revisited

Returning to the Trumpington burial clarifies the complexity of early medieval symbolism. The pendant itself is exquisite: gold sheet with garnet cloisonné, a central boss, and four radiating arms. Its craftsmanship unmistakably echoes Frankish reliquary crosses, drawing on Mediterranean Christian models that circulated among elite networks of the seventh century.

Yet its archaeological context complicates a straightforward reading. The burial lacks other overtly Christian features: there is no coffin alignment toward an altar, no adjacent church structure, no liturgical markers. The associated grave goods, though rich, are secular in type — beads, a belt set, a knife. The assemblage speaks not to monastic discipline or Christian ritual but to status, youth, and participation in elite material culture.

If the pendant marked the young woman as Christian, why do other Christian burial norms appear absent? One answer is transitional custom; burial practice often lags behind belief, especially in contexts where Christianity is only gradually taking root. But another possibility is equally compelling: political mimicry. The adoption of Christian aesthetics — crosses, garnets, Mediterranean forms — could signal proximity to the power structures of Christian Europe without requiring full theological commitment. Displaying such a cross in death might therefore communicate the prestige, alliances, or aspirations of a family as much as, or even more than, the personal faith of the deceased.

In this sense, the Trumpington Cross functions as both ornament and message. It situates the woman within continental networks of exchange while leaving faith itself open to interpretation — a reminder that symbols often travel more quickly than beliefs, and that their meanings are shaped as much by politics and performance as by devotion.

Beyond Conversion

The tendency to equate crosses with Christianity reflects a broader interpretive habit: the desire to read the early medieval past through linear narratives of transformation. For centuries, historians — following Bede’s providential framing — imagined Christianisation as a coherent, directional process in which one worldview neatly replaced another. But the archaeological record tells a different story. Rather than a single movement from “pagan” to “Christian,” we see a landscape of overlapping practices, experimental symbolisms, and shifting allegiances.

In this context, the cross operated not as a definitive marker of religious identity but as a versatile form within a wider repertoire of signs. Communities adopted, adapted, or reinterpreted Christian motifs in ways that suited local aesthetics, social aspirations, and political needs. The symbol could stabilise elite identities, express participation in continental networks, or serve as a protective emblem — without presuming doctrinal commitment.

What emerges is not a tale of one religion displacing another, but a picture of cultural bricolage. Early medieval England was characterised by negotiated identities: some devotional, others performative, many entirely ambivalent. Material culture reflects this hybridity more faithfully than textual sources do. Objects change meaning rapidly, responding to shifts in authority, fashion, and interregional contact.

This helps explain why seventh-century graves are simultaneously saturated with crosses and yet resistant to reading as straightforwardly “Christian.” A pendant might have functioned as a diplomatic gift, a marker of kinship or rank, or a visual passport into continental systems of prestige. The power of the cross lay in precisely this ambiguity. It could speak multiple languages at once — religious, political, aesthetic — offering different meanings to different audiences. Its polyphony is not evidence of incomplete Christianity, but of a world in which symbols were inherently fluid.

Reading the Cross, Reading Ourselves

When we look at a seventh-century cross, we also look at our own interpretive reflexes. The impulse to equate symbol with faith reflects a modern expectation that meaning should be fixed, legible, and singular. We want images to stand for ideas, objects to reveal belief, graves to mirror doctrine. It is an interpretive habit shaped by contemporary categories, not early medieval ones.

But early medieval material culture resists that desire for clarity. Its symbols were flexible because communities lived within overlapping and shifting horizons of meaning. Its art was hybrid because identity was continually negotiated — through contact, exchange, imitation, aspiration — rather than inherited fully formed. Motifs circulated across political, cultural, and religious boundaries with little concern for the categorical distinctions scholars later imposed upon them.

In this context, the cross was not automatically a confession. It was a medium of mediation — between ancestral practices and new ideologies, between local networks and continental powers, between personal expression and communal performance. Its significance depended on who saw it, where, and under what social conditions. Meaning was relational rather than doctrinal.

Recovering that multiplicity is not a rejection of faith where it existed, but an attempt to restore the complexity of early medieval experience. It asks us to unsettle our own assumptions about what symbols ought to do, and to recognise that belief, status, diplomacy, aesthetics, and memory often occupied the same physical form.

Crosses did not make people Christian; people made crosses meaningful — in ways that were experimental, situational, and rarely reducible to a single reading.

Want to read more? Subscribe to follow the project and its ongoing conversations.

Want to Read More?

- Carver, M. The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe, AD 300–1300. York: York Medieval Press, 2003.– Seminal collection analysing conversion as a material and social process rather than a theological moment.

- Hills, C. Origins of the English. London: Duckworth, 2003.– Discusses burial archaeology, ethnicity, and belief systems during early Anglo-Saxon England, including symbolic ambiguity in grave goods.

- Webster, L. Anglo-Saxon Art: A New History. London: British Museum Press, 2012.– Rich discussion of the aesthetic evolution of Christian motifs and their interaction with continental traditions.

- Meaney, A. Anglo-Saxon Amulets and Curing Stones. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1981.– Classic study of the interplay between religious and magical symbolism in early medieval England.

- Hawkes, S. C. “Symbol and Image in the Conversion Period.” Medieval Archaeology 32 (1988): 1–31.– Groundbreaking article unpacking the non-religious uses of Christian iconography in conversion-era material culture.

- Hines, J. “Religion: The Limits of Knowledge.” In The Anglo-Saxons from the Migration Period to the Eighth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective, ed. J. Hines, 375–410. Woodbridge: Boydell, 1997.– Excellent theoretical framing for how belief is (and isn’t) visible in the archaeological record.

- Pluskowski, A. “Paganism, Christianity and Cultural Negotiation in the Early Medieval European Frontier.” World Archaeology 45, no. 1 (2013): 4-18.– Comparative case studies on symbolic negotiation across conversion frontiers, linking to your argument about cross-iconography as cultural mediation.

- Geake, H. The Use of Grave Goods in Conversion-Period England, c.600–850. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1997.– Crucial for understanding the shift from hybrid symbolism to Christianised mortuary practice.

Leave a comment