In every ancient history module I’ve ever taken, one thing is said almost unanimously:

When a text says “servant,” the author probably meant “slave.”

That single emphasis of a linguistic substitution – servant for slave – reveals the illusion of neutrality in translation. What we inherit as “the past” has already been filtered, softened, or moralised through layers of linguistic decision-making. Translators, even when they claim fidelity, are interpreters, editors, and cultural mediators.

The Translator as Gatekeeper

Translation has never been a transparent act of communication. It’s a negotiation between worlds – between what a word meant then and what a culture can tolerate now.

When a translator in the nineteenth or early twentieth century chose to render doulos (Greek for slave) as servant, the choice wasn’t linguistic – it was ideological. To acknowledge slavery in the classical world meant confronting the moral contradictions of one’s own. “Servant” let readers keep antiquity elegant, respectable, and safely distant from the violence that underpinned it.

This softening had as much to do with the morality of the day as with the text itself.

During the height of British colonial rule, slavery – in both its historical and ongoing forms – was a politically volatile subject. To depict the Greeks or Romans as societies built on enslavement would have complicated the imperial fantasy of inheritance: that Britain was the rightful heir to classical civilisation, the new Rome.

By translating away the brutality of ancient servitude, Victorian scholars made the past “safe” – a model of order and beauty rather than domination. In doing so, they romanticised antiquity and excused empire. To present the ancients as genteel masters and their slaves as willing servants mirrored a contemporary worldview: one that justified colonial power under the guise of civilisation and culture.

It was, in short, nicer for readers – and for the translators themselves – to believe that the classical world had been noble, civilised, and free.

Language, then, doesn’t just describe power; it conceals it.

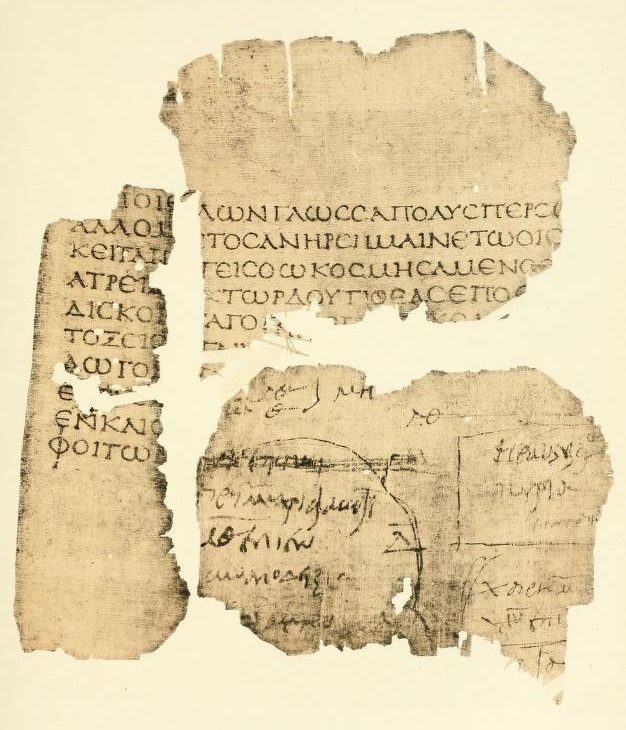

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 20 (P. Oxy. 20): containing 12 fragments of the second book of The Illiad.

Emily Wilson’s translation of The Illiad

Emily Wilson and the Shock of Accuracy

Classicist Emily Wilson, the first woman to translate The Odyssey into English, made this explicit when she published her translation in 2017. Her version stripped away the euphemism and patriarchal rhythm that had long shaped how English readers imagined Homer.

Where earlier translators called the enslaved women in Odysseus’ household “maids” or “girls,” Wilson calls them what the Greek does: slaves. Where others rendered the same women as “harlots” or “whores,” she writes female slaves – a linguistic correction that refuses to moralise their sexuality or to conflate coercion with sin.

Wilson has been clear about the principle behind such decisions: a translator always makes choices. What earlier male translators presented as “faithful” renderings were, in reality, interpretations framed by the moral vocabulary of their age. The English “whore” carries centuries of Christianised shame; in Homer’s Greek, the term is neutral, descriptive, and rooted in circumstance, not condemnation.

By refusing to replicate that inherited moralism, Wilson restores precision rather than inventing modern sensitivity. Her language reintroduces the violence of the world she translates – not by amplifying it, but by ceasing to disguise it.

Her Odyssey unsettled many precisely because it revealed what readers had learned to forget: that translation is always an act of moral framing.

“Every translator,” Wilson has said, “makes choices.”

Her choices aren’t about making Homer modern, but about making his world legible again – on its own, often uncomfortable, terms.

Gendered Language, Gendered Worlds

Wilson’s work also exposes how male translators historically projected their own worldviews into ancient texts. In earlier translations of The Odyssey, Penelope is “cunning,” “scheming,” or “faithful to a fault.” In Wilson’s hands, she is “thoughtful.”

A single adjective reframes a millennium of interpretation.

When translators described women as “treacherous” rather than “strategic,” or men as “noble” rather than “arrogant,” they weren’t merely reflecting linguistic differences—they were reinscribing cultural hierarchies.

Translation becomes a mirror, not of the past, but of the translator’s ethics.

The Residue of Words

Every word carries residue. To translate is to choose which residues we keep.

When we read Homer, the Gospels, Beowulf, or medieval chronicles in English, we inherit a past already moralised for us.

Terms like servant, faith, honour, and virtue have each shifted meaning – not once, but many times – as translators and copyists adapted texts to new audiences. What began as a term of bodily servitude could become one of spiritual obedience; what once meant public reputation became moral integrity. Each shift smoothed over a violence, a hierarchy, or a material truth the original world would have taken for granted.

Even now, translation remains political: which terms get italicised, which stay foreign, which are domesticated into comfort. The historian or classicist reading in translation is always reading someone else’s ethics.

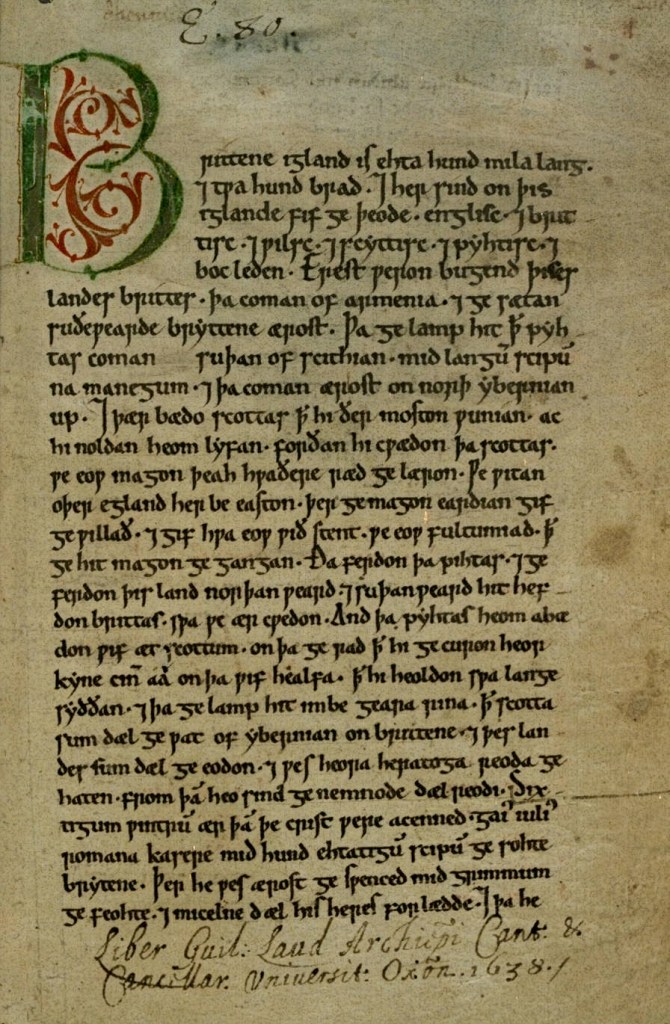

The initial page of the Peterborough Chronicle ASC E.

Medieval Translators and the Reinvention of Meaning

The Middle Ages were not passive recipients of classical texts – they were their retranslators. Few medieval authors saw translation as reproduction; it was interpretation, often revision.

Anglo-Saxon scholars, for instance, translated Latin texts into Old English with as much invention as fidelity. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle – a record of history copied, expanded, and adapted for more than two centuries – shows how even within a single language, translation was never neutral.

Different monastic centres preserved different versions; some emphasised regional rulers, others moralised events through divine causation. A battle might be framed as a test of faith in one manuscript and as a political victory in another. These were not deliberate acts of propaganda so much as reflections of local perspective – what each community thought history should remember.

Even when a scribe intended to be factual, their choices of phrasing, omission, or emphasis made the Chronicle an argument about meaning. Neutrality itself was interpretive.

What modern editors call “translation,” medieval readers experienced as conversation – a dialogue across centuries in which every copyist became, consciously or not, a co-author. In medieval Europe, translation was creation, and even attempts at preservation became acts of reinterpretation.

Reading in English

To recognise that translation isn’t neutral isn’t to dismiss it – it’s to read more attentively. The task isn’t to find purity but to see the scaffolding.

When we read Wilson’s Homer, or any translation that reclaims uncomfortable language, we’re being invited not just to revisit an ancient world but to notice the filters we’ve inherited – grammatical, cultural, and moral.

Yet English is only one of those filters. Every language has its own habits of hierarchy, gender, and tense; its own ways of framing agency and emotion. Some are more precise in differentiating types of possession, others in distinguishing shades of respect or power. These grammatical architectures shape what a translator can and cannot reproduce.

A Latin verb can imply both command and suggestion; an Arabic root can encode moral weight in a way English cannot. Even when translators work with complete integrity, their language may nudge the reader toward one interpretation and away from another. The result isn’t inaccuracy so much as bias by syntax.

Other modern languages wrestle with this too – French and Italian with their gendered nouns, Japanese with its social registers. Each offers possibilities English does not, but each constrains in turn. Translation, then, is not merely a moral act; it is a structural one. The translator works not only between cultures but between grammars, carrying meaning through architectures that fit imperfectly together.

To read in English – or in any language not the original – is to read through the choices of those who decided what could, and what could not, be said.

Translation is an act of hospitality: opening the door to another culture – but also deciding what the guest is allowed to bring in.

Want to Read more?

- Boethius. The Consolation of Philosophy. Translated by S. J. Tester. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973.

- Emily Wilson. The Odyssey. Translated by Emily Wilson. New York: W. W. Norton, 2017.

- D. S. Brewer (ed.). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Collaborative Edition. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1983–2004.

- George Steiner. After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998 [1975].

- Rita Copeland. Rhetoric, Hermeneutics, and Translation in the Middle Ages: Academic Traditions and Vernacular Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Leave a comment